|

KEY STEPS IN ENVIRONMENTAL MAINSTREAMING

IN BRIEF

Key steps in environmental mainstreaming

Although mainstreaming is not a standardised, technical process carried out in a neat sequence, we can still identify typical steps that commonly characterise effective environmental mainstreaming, from good practice to date.

- Scope the political economy and governance affecting environment and development;

- Convene a multi-stakeholder group to steer the mainstreaming process;

- Identify links between development and environment, both positive and negative;

- Propose desirable environment-development outcomes;

- Map institutional roles and responsibilities for each of the links and desirable outcomes;

- Identify associated institutional, governance and capacity – and changes required;

- Identify entry points for environmental mainstreaming in key decision-making processes;

- Conduct expenditure reviews and make the ‘business’ case for environmental inclusion;

- Establish or use existing forums and mechanisms for debate and consensus;

- Reflect agreed changes in key mainstream policy, plan and budget documentation;

- Promote key investments in development-environment links;

- Develop integrated institutional systems and associated capacities;

- Install criteria/indicators and accountability mechanisms to ensure monitoring and continuous improvement in environment-development integration.

These steps will gradually develop the capacities, systems and skills needed to mainstream environment on a continuing basis. |

In Chapter 6, we asserted that environmental mainstreaming is not a mechanical exercise which would follow a clear ‘recipe’, and offered some general principles to guide the work towards clear outcomes (section 6.1). We can, however, illustrate the kinds of basic steps that might then follow, to be undertaken as far as possible within an existing mainstream national, sectoral or local analytical/planning process (Box 22.1).

Box 22.1: Typical steps in environmental mainstreaming

The precise steps will depend upon the standard programmatic (cyclical) requirements of the analytical/planning process concerned. Typical steps for a comprehensive national process, from good practice to date may include:

-

Scope the political economy and governance structures affecting environment and development – who is making decisions and for whom, who is benefiting, who is bearing costs and risks – and associated motivations and incentives.

-

Convene a multi-stakeholder group to steer the mainstreaming process. This should combine environment and development interests as well as those who bridge the interests – to act as ‘champions’ for environmental mainstreaming, track progress, and provide policy and other recommendations to government, etc. Composition will be informed by 1 above. The format might be a National Councils/Commissions for Sustainable Development [link to tool profile] as established in many countries, or an informal ‘learning group’ [link to learning group menu item], as developed by IIED.

-

Identify the current links between development and environment, both positive and negative. This could be expressed, e.g. in terms of how specific environmental issues or initiatives help to achieve or inhibit progress towards each of the MDGs (or in terms of benefits such as incomes, livelihoods, health, safety net, growth, etc.); or how development initiatives support or impair particular ecosystem services. In some countries, national wealth accounts can be used to illustrate the relative significance of environmental assets.

-

Propose desirable environment-development outcomes and clarify how they differ from the current links – their potential to open up and develop environmental opportunities or tackle key environmental constraints or hazards.

-

Map institutional roles and responsibilities for each of the links and desirable outcomes (by spatial level, or by sector) – identifying synergies as well as lacunae/clashes.

-

Identify associated institutional, governance, and capacity changes required to improve outcomes and evolve more appropriate roles and responsibilities. As far as possible, diagnose the current levels of capacity (see Chapter 7).

-

Identify relevant entry points for environmental mainstreaming in key decision-making processes, informed by the above. National planning, public sector reform, and aid planning processes can all offer effective entry points.

-

Conduct expenditure reviews and make the ‘business’ case for improving environmental inclusion in each of the specific links (benefits, costs, risks and their distribution – in financial terms as far as possible and where relevant) and feed this into the ‘entry points’.

-

Establish or use existing forums and mechanisms to put the above to public/multi-stakeholder debate and to agree on/build consensus on what needs to be prioritised e.g. national planning procedures, or donor coordination mechanisms such as the UNDAF.

-

Reflect agreed changes in key mainstream documents that have a recognised mandate – notably (a) policies, (b) strategies, plans and programmes, and (c) budgets. In general (but not exclusively), the more ‘upstream’ the better e.g. fiscal policy rather than one financial instrument.

-

Promote key investments in development-environment links that pass cost-benefit tests – by government, private sector and civil society – especially where these contribute directly to key sectors in the national/local economy.

-

Develop integrated institutional systems and associated capacities – for coordination, management, financial, information and communication, and monitoring systems – so that they incorporate environment on a sustained basis.

-

Ensure responsible organisations are accountable – develop/adopt a clear set of indicators that measure if a society or initiative is truly based on sustainable development principles and ensure these measurements can hold organisations accountable and support continuous improvement.

|

As an institutional change process, environmental mainstreaming will take time and will be iterative. Some initiatives group the various steps into phases, typically assessment, planning, capacity building and continuing implementation (e.g. PEI 2008 [link to references]and Box 22.2 for drylands).

Box 22.2: Generic steps for drylands mainstreaming

UNDP guidelines (2008) suggest broad generic steps for mainstreaming environment and drylands issues into national development frameworks.

Strategic assessment phase

Step 1 Identifying and analysing the status of land issues and their environmental, economic and

social impacts, taking into account the various direct and indirect drivers of change affecting

land issues;

Step 2 Identifying and filling information needs/analysis;

Step 3 Assessing the legal, political and institutional environment for mainstreaming;

Step 4 Conducting stakeholder analysis and defining roles, responsibilities and obligations;

Step 5 Carrying out capacity assessment.

Awareness, participation and partnership-building phase

Step 1 Drawing up a communication and awareness creation strategy;

Step 2 Building partnerships for mainstreaming;

Step 3 Planning for participation and consultation processes.

Planning phase

Step 1 Undertaking iterative and integrative planning;

Step 2 Linking the plans to budgets and funding mechanisms

Implementation phase

Step 1 Building capacity

Step 2 Implementing the plans

Learning, monitoring and evaluation phase

Step 1 Monitoring and evaluation of planning frameworks for impacts;

Step 2 Evaluation of the effectiveness of mainstreaming processes;

Step 3 Revision of the planning frameworks

Source: UNDP (2008) |

However, the approach taken does not have to be fully comprehensive, i.e. covering all the steps listed in Box 22.2 for all environment-development issues at any one time. It can be more tactical to begin to tackle the broad agenda through an initial focus:

To focus on significant environment-dependent stakeholders that have been relatively marginalised to date, e.g. empowering civil society to express a breadth of issues (a common tactic by environmental NGOs);

To focus on particular sectors or districts that have already expressed the need for environmental action and ‘feel the burn’ to act, e.g. commonly health, energy and infrastructure;

To focus on one priority environmental theme or resource where there is already a broad consensus on potentials for change but not necessarily yet the institutional, technological or fiscal solutions e.g. transition to a low-carbon economy;

To focus on one particular mainstreaming tool or procedure to open up the issue e.g. to subject key plans to EIA or SEA, or to bringing together the leaders/authors and major stakeholders of major policies, plans, strategies and programmes collectively to examine the consistency of such documents.

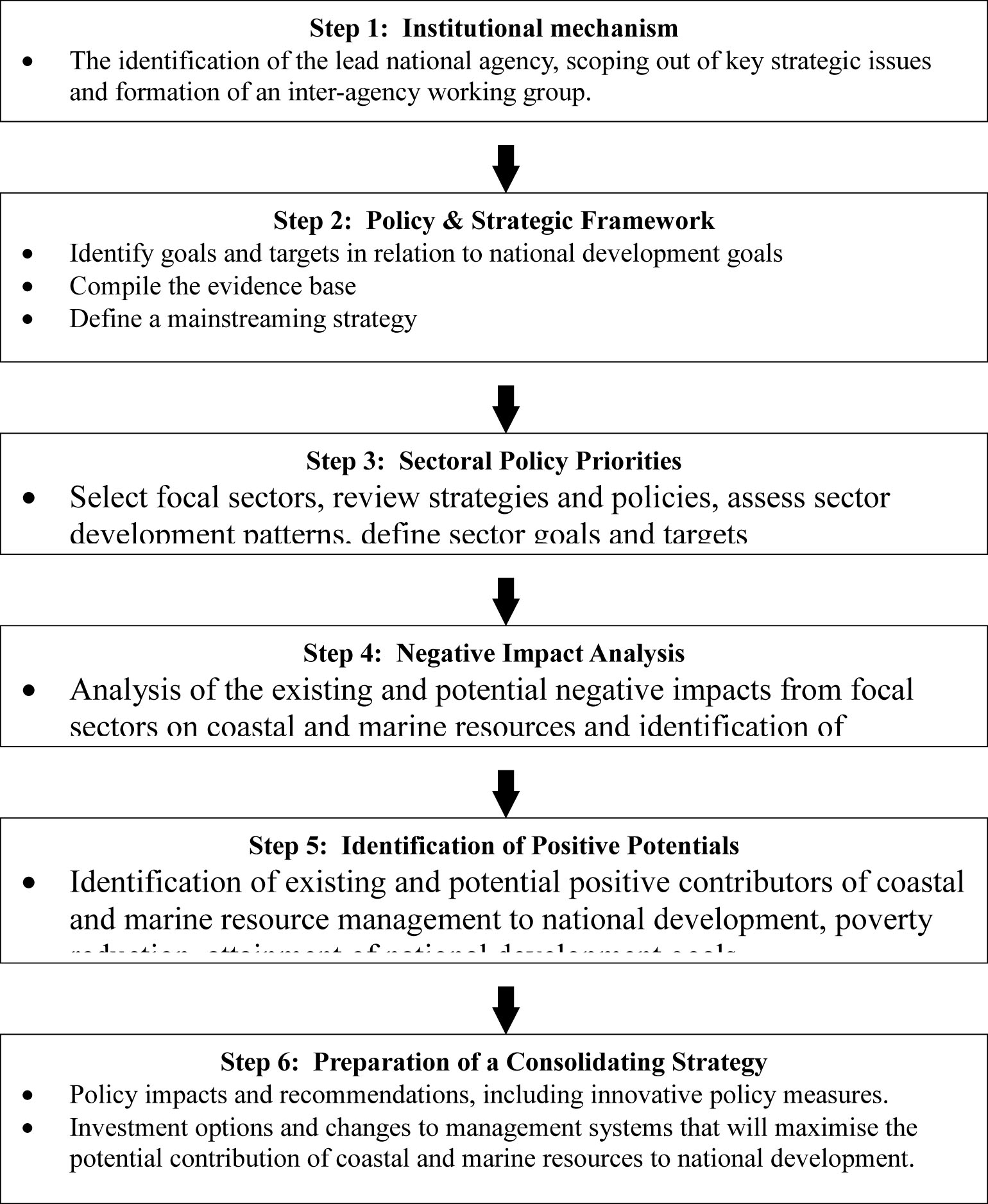

UNEP’s Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA) has prepared an analytical framework to mainstream issues concerned with the management of marine resources and coastal areas and guidelines (both for countries with an existing National Programme of Action and new countries) plus a checklist of questions for operationalising the framework (Soussan 2007). The framework sets out 6 key mainstreaming steps (Figure 22.1) [link to figure]and notes two overall challenges in the mainstreaming process (Box 22.3) [link to box]:

Figure 22.1: The sequencing of steps in the mainstreaming process for marine and coastal

issues

(Source: Soussan (2007))

Box 22.3: Challenges to mainstreaming coastal and marine issues

UNEP notes two overall challenges in the mainstreaming process:

-

“National planning and budgetary processes tend to focus on factors that will stimulate growth and development, whereas the natural focus of measures to protect marine resources from land-based activities is on regulatory and safeguard measures that are restrictive in character: they are intended to modulate development activities and limit the impacts of different sectors on the esource base. Reconciling development pressures with protection objectives is a fundamental equirement of any framework for these issues.

-

The character of measures to protect marine resources from land-based activities is that they are not a bounded sector in themselves, but rather relate to aspects of a wide range of other sectors: fishing, tourism, coastal transport, environmental conservation, water management, coastal zone development and so on. This means that such measures need to be translated into a set of sectoral measures and will involve a wide range of institutions and stakeholders. Establishing the policy and institutional context of any approach to mainstreaming is consequently a challenge in itself.

The identification of how marine and coastal resources issues can be mainstreamed into national planning and budgetary processes must reflect these twin challenges, developing national strategies to balance development and conservation needs and creating mechanisms that ensure effective integration across sectors. The nature of development planning and budgetary processes and institutional mandates in relation to coastal and marine resources are both variable from country to country, with responsibilities often fragmented across a number of agencies.

The integration of coastal and marine issues into overall development processes needs to be based on good coordination between institutional structures that are often fragmented and partial in their coverage of some key issues. This is compounded by the tendency of many people and agencies not to see the maintenance of the environmental integrity of coastal areas as their main concern: they are more focused on tourism development or fish catches or farming production.

This does not mean that they are not interested in preserving the coasts, but more that this is secondary to their main responsibilities, which are often to increase economic development. They are willing to support actions to reduce the impact of their sector on the coastal and marine environment so long as it does not cost too much or disrupt the operation of the sector they are concerned with in an unreasonable way. They are potentially allies for protecting the coasts and will be willing collaborators in ensuring more coherent and strategic approaches to achieving this. The framework presented here build towards creating this “constituency” so that coastal and marine resource issues are championed in the overall national development process”.

Source: Soussan (2007) |

|